Today, “sacred” is a broad and generously deployed word. Sporting areas are sacred, bedrooms too. The English word emerged in the late Middle Ages to connote the bread and wine of Eucharist, but its Latin root, “sacer,” held a double meaning, gesturing both to places or objects capable of wreaking spiritual pollution and those restricted for divine use.

The Romans enjoyed sealing spaces off from the “profanum” and bringing them under the state’s control. For the barbarian sites of sacredness they encountered, however, they were at best indifferent (Stonehenge) and at worst destructive (the Temple of Jerusalem). One need only think of the Keystone Pipeline XL protests or the fate of the Benin Bronzes to remember such tendencies endure.

Inside Sacred Sites. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

If there is universally sacred space, it’s the earth itself. This is the starting point for Sacred Sites, the latest colorful tome in Taschen’s “The Library of Esoterica” series. There on the front cover is Earthrise, astronaut William Anders’s 1968 photograph that offers our planet as a vulnerable thing of wonder.

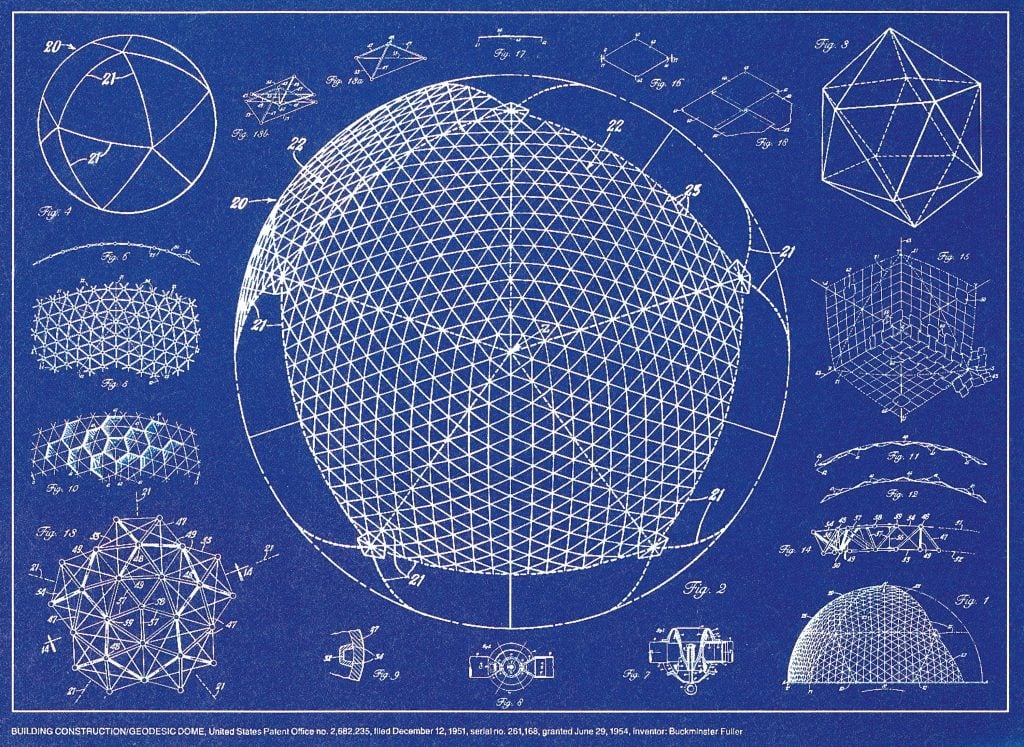

Buckminster Fuller, Building Construction/ Geodesic Dome, United States, 1951. Photo: courtesy Taschen.

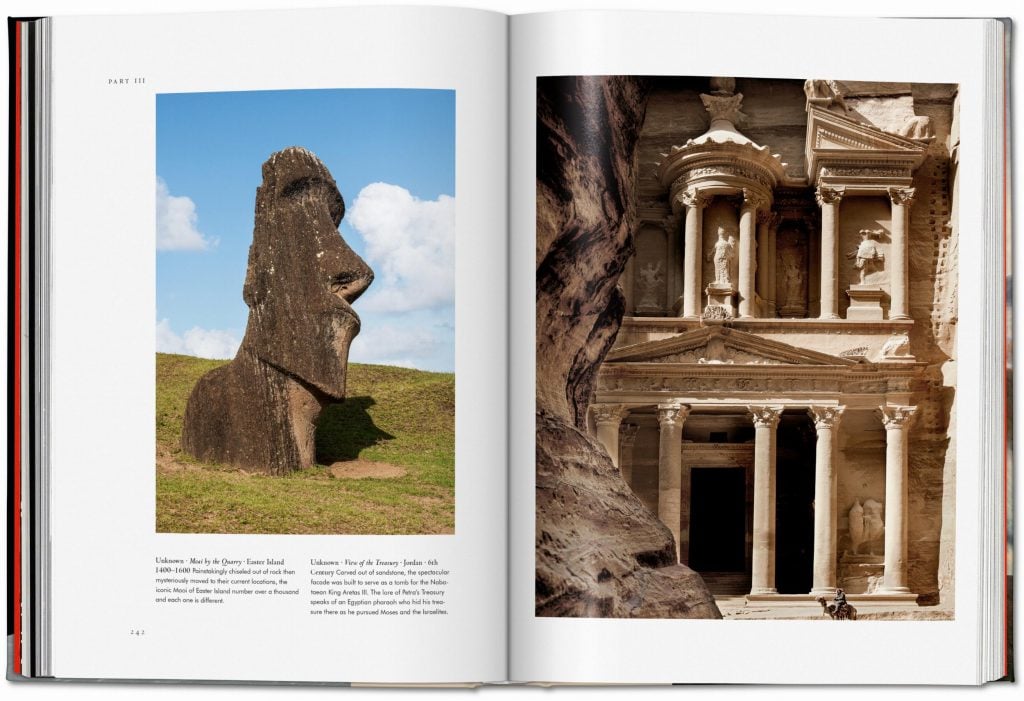

The project is a broad one: to offer up the innumerate places considered sacred by humans from the Neolithic-era through today. “Tracing a hallowed route from rugged stone temples to transcendent works of modern architecture,” editor Jessica Hundley wrote in the preface, “this volume celebrates the collective history of spaces made sacrosanct through human worship.”

Inside Sacred Sites. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

This journey begins with a sampling of global civilization’s greatest architectural hits. It runs through the Great Sphinx, Stonehenge, Machu Picchu, Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall, Sagrada Familia, offering short biographic information on each. Lesser known offerings include the Minaret of Jam, a 200-foot brick tower built by the Ghurids 800 years ago, and 12th-century Puebloan cliff dwellings in modern-day Colorado.

Mohammadreza Domiriganji, Ceiling of Vakil Mosque, Shiraz · United Arab Emirates · 2014. Photo: courtesy Taschen.

“Earth Body” follows, it’s a chapter devoted to mankind’s eternal worship of earth and nature. It introduces earth, stone, water, sky, mountains, forests and groves, and caves and grottos, presenting artistic representations for each. We meet Van Gogh’s cerulean skies, Georgia O’Keeffe’s twisted animal bones, and Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic classic.

In addition to earth worship, “Sacred Sites” proposes body worship as “perhaps the most ancient of all spiritual practices”. Greek, Egyptian, Mesoamerican and Hindu fertility temples present physical evidence, as does artwork spanning Greek Colossal Phallus sculpture, medieval manuscripts, Qing dynasty erotica, and contemporary body art.

Olafur Eliasson “The Weather Project · Iceland/ Denmark”, 2012. Photo: courtesy Taschen.

In “Architecture of the Spirit” we encounter the dominate and recurring shapes and geometries of manmade sacred structures. There’s the pyramids, spanning Egypt, Mesoamerica and the Louvre, the domes of Turkic crypts and Taj Mahal, and the circles of Buddhist shrines, Venetian pleasure gardens, and Ethiopian village houses.

Yann Arthus-Bertrand “Moshav (co-operative village) farm at Nahalal, Jezrael plain, Israel”. Photo: courtesy Taschen

The final chapter of “Sacred Sites” is largely devoted to the ways in which the “landscapes of fiction and myth, of folk tale and song,” have been made real by artists and intentional communities. From the fantastical visions of Hieronymus Bosch, Denis Villeneuve, and William Blake, we arrive at the geodesic domes of Osaka Expo Japan, photographs of rigidly planned urban areas and those of towering libraries, the artificial sun of Olafur Eliasson. In each we find wink of a promise that paradise, as the book promises, can be found.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: