As I write on Friday morning, the telltale auction week is largely done and dusted, with just a couple of lower-value day sales at Christie’s wrapping up later this afternoon.

The total haul so far is $1.2 billion, just clearing the low end of the week’s presale range. That total includes buyer’s premiums, while the estimates do not. And it does not reflect all the drama and auction wizardry that happened behind the scenes to achieve such relatively positive optics.

Reserves were lowered at the 11th hour, irrevocable bids negotiated within minutes of sales, some lots withdrawn, and others reopened after having failed to sell. The houses deserve credit for pulling it off.

There’s clearly appetite to buy at the very top of the market, when quality and historical significance align, as René Magritte’s $121 million record at Christie’s demonstrated. At a lower price point, buyers went gaga for Keith Haring’s “subway” drawings, snapping up all 31 of them for $9.2 million at Sotheby’s.

A salesroom at Christie’s auction on November 19 in New York. Photo: Katya Kazakina

Tight, high-quality single-owner evening sales of the estates of Mica Ertegun and Sydell Miller were sold 100 percent by lot. Miller’s gorgeous Monet sparked a 17-minute bidding war, selling for $65.5 million to an Asian collector. Chinese crypto entrepreneur Justin Sun paid $6.2 million for a banana.

Elsewhere, the results were mixed. The market showed itself to be highly selective and price sensitive. Collectors wanted deals. Bottom feeders drove up prices wherever the estimates seemed like a bargain.

Take Thomas Houseago’s 2012 bronze owl at the Phillips day sale, which was estimated at $60,000 to $80,000, and ended up selling for $330,000. A few lots earlier, a Cecily Brown work on paper, Untitled (Young Spartans), 2015, fetched $279,000, more than three times its low estimate of $80,000.

Of the seven evening sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips, two exceeded their presale targets, two fell short of their low estimates, and three were within their expected ranges. Of course, we are comparing apples and oranges because the final prices recorded by the houses include their steep buyer’s premiums, which can add as much as 26 percent on top of the hammer price, while the estimates don’t. These premiums give the houses some wiggle room since they can tap into them to make deals happen.

Sotheby’s auctioneer Oliver Barker overseeing the bidding for Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian (2019) at Sotheby’s on November 20. Photo: Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Not surprisingly, much of the material in the evening sales was presold through irrevocable bids as a way of ensuring a high sell-through rate, a key metric auction houses use to win consignments. Sellers have to give up part of their potential haul to pay for these commitments. As the week revealed price resistance for certain artists, even bullish sellers accepted irrevocable bids—or decided to withdraw their lots to avoid having them fail on the block.

For example, after lots by Jeff Koons failed to sell at Sotheby’s (Women in Tub, 1988, est. $10 million-$15 million) and Phillips (Christ and the Lamb, 1988, est. $600,000-$800,000), consignors of Koons works at Christie’s accepted third-party guarantees. (More on that later.)

Many of the works that hadn’t been pre-sold (or withdrawn) passed.

High-profile casualties of the week included a $10 million Basquiat at Phillips, the Koons at Sotheby’s, and a Picasso at Christie’s. But there were many others, and the sell-through percentages at the three various-owners evening sales were in the 70s, not the desired outcome by any measure.

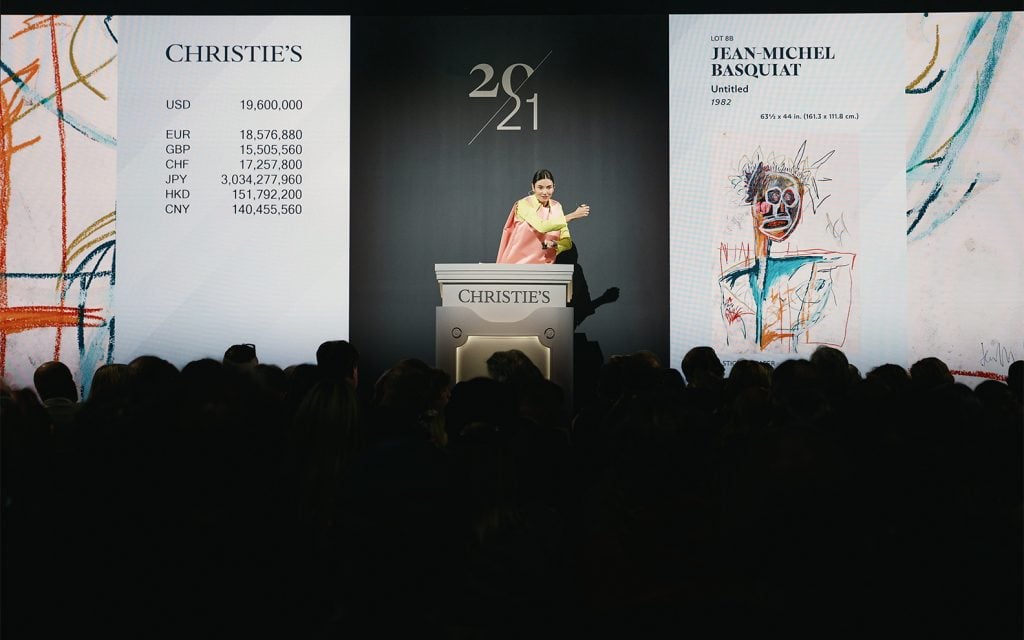

Georgina Hilton sells the top lot of Christie’s 21st-century sale, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled for $22.9 million. Courtesy of Chrisite’s.

Last week, I identified 11 lots being offered by Peter Brant, a newsprint magnate and powerful collector. The performance of his lots encapsulates the market conditions and collector behavior.

The priciest of the group was an untitled 1982 drawing by Jean-Michel Basquiat that is believed to be one of his largest and most significant works on paper. Aggressively estimated at $20 million to $30 million (considering that the auction record for a work on paper by Basquiat is $15.2 million), it hammered at $19.6 million at Christie’s 20th-century evening sale. The buyer was Alberto Mugrabi, as my colleague Eileen Kinsella reported.

Brant was so confident in the work’s desirability that he didn’t take a guarantee by the house or third-party.

Brant accepted a last-minute third-party guarantee for his Koons, New Hoover Celebrity IV, New Hoover Convertible, New Shelton 5 Gallon Wet/Dry, New Shelton 10 Gallon Wet/Dry Doubledecker (1981-86). Two bidders went after the gleaming set, and the work sold for $5.1 million, within its estimated range of $3.5 million to $5.5 million.

Jeff Koons, New Hoover Celebrity IV, New Hoover Convertible, New Shelton 5 Gallon WetDry, New Shelton 10 Gallon Wet/Dry Doubledecker, 1981-86. Photo: Courtesy Christie’s

Brant withdrew his third work in the sale—Eric Fischl’s record-setting paintingThe Old Man’s Boat and the Old Man’s Dog, estimated at $3 million to $4 million—presumably for lack of interest. The collector agreed to lower the reserve on the fourth work, Roy Lichtenstein’s George Washington. Estimated at $7 million to $10 million, it hammered at $5.8 million.

Brant’s lower-value lots at Sotheby’s were a mixed bag, as well. Richard Prince’s self-portrait got withdrawn. Paintings by Christopher Wool and Enoc Perez failed to sell.

Three Brant works hammered at or below their low estimates, including a small sculpture by Simone Leigh, titled Blue/Black (2014), which Brant bought for $750,000 just two years ago at Sotheby’s summer sale in London. This time around, the work hammered at $360,000.

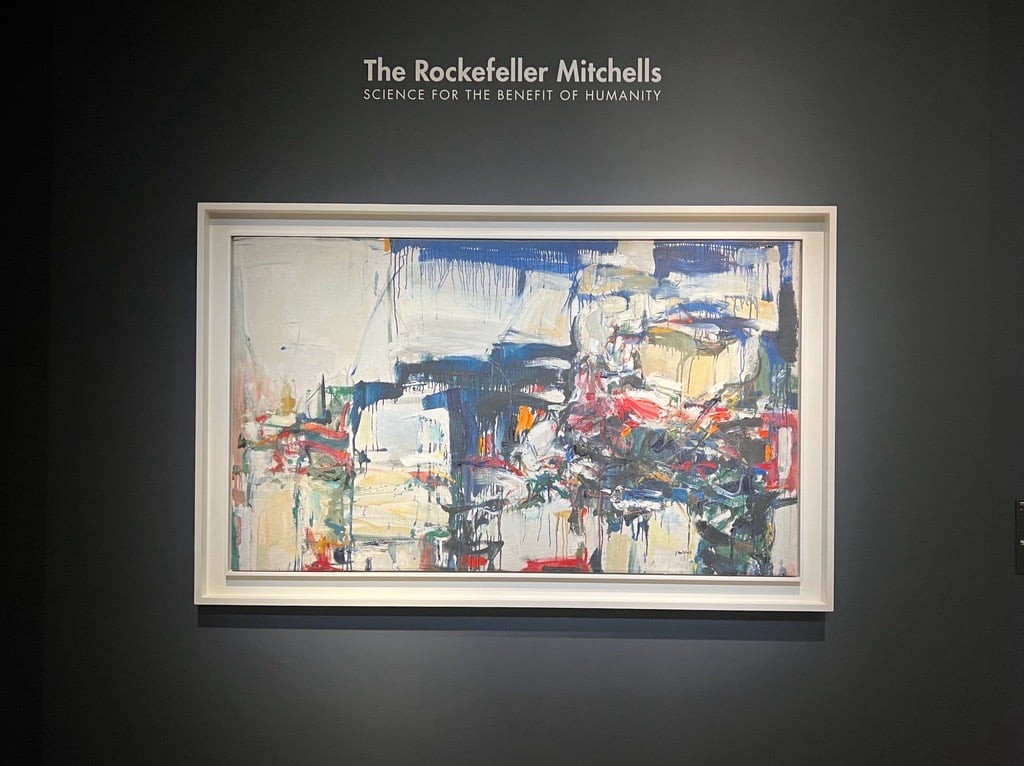

Joan Mitchell, Untitled, 1955, from the Rockefeller University at Christie’s. Photo: Katya Kazakina

Brant fared much better than fellow collector Ron Perelman, whose two works—by de Kooning at Christie’s and Twombly at Sotheby’s—failed to find buyers.

The houses didn’t cover all of their guarantees with irrevocable bids, and it cost them when some of those lots failed to sell, including the $12 million Matisse and the $10 million Koons at Sotheby’s. Christie’s barely avoided a disaster, as well, with two Joan Mitchell paintings it had guaranteed to the Rockefeller University. Neither was getting any traction for several long moments. It looked like they would be bought-in, setting the house back some $24 million. Then, thankfully, deputy chairman Xin Li-Cohen swooped in and saved the day, acquiring both paintings below their low estimates with the same paddle, number 2155.

There were some bright spots, including a group of abstract works from the collection of Thomas Armstrong at Sotheby’s. The visionary museum director spent 16 years at the helm of the Whitney Museum of American Art, acquiring seminal paintings by Jasper Johns and Frank Stella, as well as Calder’s Circus (1931).

Myron Stout, Apollo (1955). Courtesy: Sotheby’s

Designated as “A Singular Vision: The Collection of Thomas N. Armstrong III & Whitney ‘Bunty’ Armstrong,” it included 21 works (mostly geometric abstractions), all of which sold for a total of $1.7 million, more than twice the presale high estimate of $781,000. Seven new artist records were set.

The top lot was Apollo, a stark 1955 painting by Myron Stout with a biomorphic white shape on black background. Considered a bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism, Stout (1904–87) was “a legendary—if not mythic—figure of contemporary art,” according to Sotheby’s. Yet, his auction record until this week was just $74,800. Which is why Sotheby’s presale estimate of $300,000 to $500,000 got my attention. The final price of $900,000 left those numbers in the dust.

The rest of the group did well in the day sale. Armstrong’s blue-and-black painting by Ray Parker fetched $132,000, more than 10 times its low estimate of $10,000. A lyrical Paul Feeley, titled Carthage (1962), sold for $336,000, surpassing its presale estimate of $60,000 to $80,000. Leon Polk Smith’s Red Black White (1948), estimated at $30,000 to $50,000, fetched $180,000.

One lucky bidder paid just $3,000 for Andrew Masullo’s 2006 composition 4960, which was offered without a reserve. That’s a bargain if ever there was one.

Let’s hope that this week’s results will provide a floor for the market, give some confidence to collectors, and inspire high-quality consignments in the coming months.