The Step Pyramid of King Djoser, on the Saqqara plateau in northern Egypt, is an awesome feat of engineering, and experts still do not understand the techniques used to erect it.

Built about 4,500 years ago, it is the oldest of the seven major pyramids, standing more than 200 feet high and including stones that weigh more than 650 pounds. The structure pioneered the pyramidal form for what are generally considered to be the graves of the pharaohs as well as the technique for raising stones and stacking them with precision. It was so revolutionary that its architect, Imhotep, was actually named, becoming the first of his profession whose identity is known to history.

A team of nine experts from French universities and research centers, led by Xavier Landreau of the private French research organization CEA Paleotechnic Institute, has published a new paper in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One, advancing a bold new hypothesis on how the pyramid was built.

They pointed out that experts have worked to identify the building techniques used to create these incredible structures, including ramps, cranes, and winches, but say that they were generally studying smaller, later structures that are better documented. What’s more, they argued, there has been very little multidisciplinary analysis calling on disciplines such as hydraulics, geotechnics, and paleoclimatology, of the sort that they bring to the table.

Landreau and his colleagues said that their research into an enigmatic nearby structure has led to a controversial hypothesis. This previously unexplained massive edifice, the Gisr el-Mudir enclosure, may have been a dam, they argued.

The topography of north Saqqara, showing Gisr el-Mudir at left and the Djoser Complex at right. Courtesy PLOS One.

There may have been a temporary lake west of the complex, and there may have been water flow inside a “dry moat” that surrounded it, they said. That dry moat, they explained, exhibits a monumental, linear rock-cut structure with successive, deep compartments; it has all the technical requirements of a water treatment facility, namely a settling basin, a retention basin, and a purification system that would have filtered out sediment. This way, the Gisr el-Mudir and the dry moat could work as a hydraulic system to heighten water quality and regulate its flow.

The most unprecedented finding of all, they argued, may be that the Pyramid of Djoser’s internal structure has the characteristics of a hydraulic elevation mechanism.

The ancient Egyptians are already renowned, they pointed out, for their mastery of hydraulics for uses like building canals to irrigate farmland and employing barges to transport huge stones. Some experts even refer to them as an “early hydraulic civilization,” the paper added.

A sketch of the hydraulic lift principle. Courtesy PLOS One.

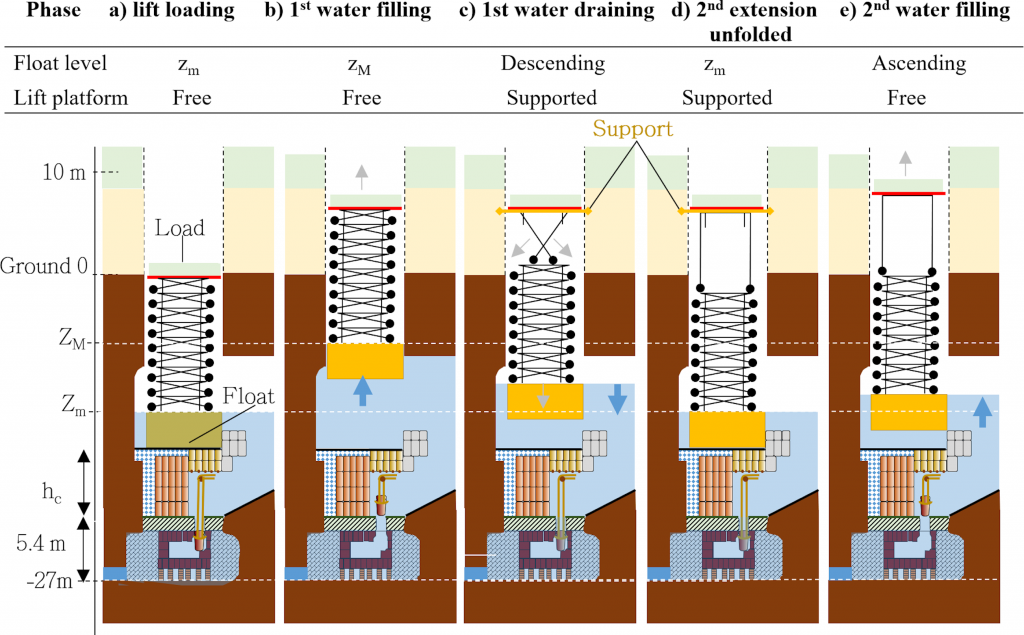

In the scheme suggested by Landreau and colleagues, water entered a vertical shaft, allowing a pulley system to raise a float and lower a platform. Workers could then have placed the rocks on the platform and drained the shaft, which would have, in turn, lowered the float and raised the platform.

This new argument actually undercuts the long-held assumption that all the pyramids were tombs. This belief has been maintained though no such figures have been uncovered and some of the rooms in question have no funerary attributes such as funerary hieroglyphs or paintings that would support interpreting these structures as tombs, says the new paper. Other experts have proposed non-funerary purposes, pointing partly to layouts and technical features for some structures that would be unnecessarily complex or irrelevant for tombs, the paper says.

“This is a watershed discovery,” Landreau told Live Science (pun intended or not). “Our research could completely change the status quo. Before this study, there was no real consensus about what the structures were used for, with one possible explanation being that it was used for funerary purposes. We know that this is already subject to debate.”

The paper is not without its detractors.

“My biggest concerns about the study are that no Egyptologists or archaeologists were directly involved and that the authors actually question the use of the Djoser Pyramid as a burial site,” Julia Budka, an archaeologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, told Live Science. “Scientifically, their hypothesis is not proven at all.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: